What is the truth of recent claims in Spinoff by Roger Douglas, the Minister of Finance from 1984-88 in the Labour Government of that time, that the free-market revolution that he helped implement was necessary and proven successful in getting the economy to compete more effectively in the world?

He argued in Spinoff that New Zealand reaped a harvest in terms of increased productivity in the mid-90s, he said. “That was the period where New Zealand started to prosper. The reason we went backwards after that was there was no change after 1991-1992. We got the benefits during the mid 1990s – we were actually ahead of Australia on productivity, the only time in 60 years that that had occurred.”

The opposite is true. As I wrote in a booklet called “Exposing Right Wing Lies” in 2012:

Instead of the gap closing with Australia, the neoliberal reforms led to a collapse in growth rates, slowing productivity growth, and widening the income gap with Australia and other OECD countries.

According to the NZ Herald columnist Brian Gaynor’s Blog the most recent data shows “Average weekly earnings have increased by 89% in Australia since mid-1994 and by just 64% in New Zealand. As a result the gap between average earnings in the two countries, in NZ dollar terms, has risen from $233 to $576 per week.”

The Dalziel paper quoted earlier also shows that the economic shocks of the period took New Zealand from a situation where the gap in GDP per capita with Australia nearly doubled from 17% in 1984/5 to 31.5% in 1992/93. Since then the gap has continued to widen. He writes:

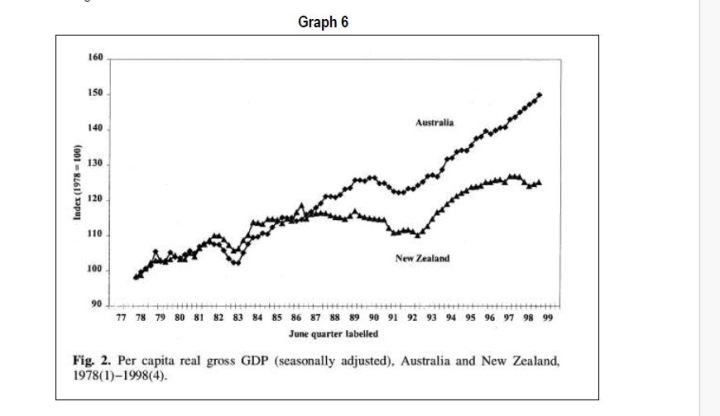

“Figure 2 [Graph 6 below] presents quarterly index data for Australia’s and New Zealand’s per capita real GDP (seasonally adjusted) from March 1978 to December 1998, with both series scaled to equal 100 for the calendar year 1978. The graphs show the two economies following a very similar growth path until the end of 1981. The world recession of 1982 then had a larger impact on Australia than New Zealand, but Australia had made up the lost ground by September 1985. New Zealand experienced a temporary two-quarter surge in GDP in 1986 (associated with the introduction of its indirect tax, the Goods & Services Tax, on 1 October); otherwise, the two series are again similar until June 1987, which marked the beginning of a widening divergence between the Australian and the New Zealand data…..

“The cumulative effect of this divergence is very large. By 1998, the value of the real output index for Australia in Fig. 2 [Graph 6] was 18.5% higher than that of New Zealand. Since per capita nominal GDP in New Zealand that year was NZ$25,980, this suggests that every New Zealander could have received an extra $4806 in 1998 if their country had continued to grow at the same rate as Australia after June 1987. This is a very large figure, amounting to just over $18 billion in the aggregate. Over the entire 1987–88 period, the sum of the Australia–New Zealand differential equals 1.16 times New Zealand’s total per capita GDP in 1998; that is, $30,000 per person or $114 billion in the aggregate. These statistics demonstrate that, compared with Australia, New Zealand sacrificed a large volume of real per capita GDP after 1987.” (see Graph 6)

Dalziel also documents a similar divergence in labour productivity between New Zealand and Australia.

“The most surprising data are in Fig. 7 [Graph 7], which shows real GDP divided by the number of full-time equivalent workers employed, rescaled so that the 1978 calendar year values equal 100. From March 1978 to September 1984, the two series are almost indistinguishable. For the next 4 years, New Zealand’s labour productivity index lies below that of Australia (except for the quarters affected by the introduction of the Goods & Services Tax in the middle of 1986), but catches up by the beginning of 1989. The series are then indistinguishable again until December 1990, after which labour productivity growth falls away in New Zealand compared with Australia (especially after December 1991). Over the last 8 years of the sample, the gap increased substantially, so that between 1990 and 1998 workers in Australia increased their productivity by 21.9 percentage points whereas the increase in New Zealand over the same period was only 5.2 percentage points. Figure 7 shows that since 1992 labour productivity growth in New Zealand has been considerably below that of Australia, after similar rates for the previous 14 years.” Dalziel concludes with an obvious point: “This observation raises profound questions for New Zealand policy makers about the effectiveness of labour market reforms intended to raise labour productivity.” (see Graph 7)

Economic historian Brian Easton estimates that New Zealand’s GDP per capita as a percentage of the OECD average went from 98% in 1986 to 84% by 1993.